Weather radar is a common tool we see everywhere, from tv to the internet to apps on our smartphones and watches. We know to look for where we are on a map and the brighter the color, the heavier the precipitation that is coming. Have you ever wondered how to read these radar images more effectively for your use? This series called Doppler Radar will look at the main aspects meteorologists use when watching storms on radar to forecast heavy bands of precipitation as well as hail, thunder storms and tornadoes in the summer months

.

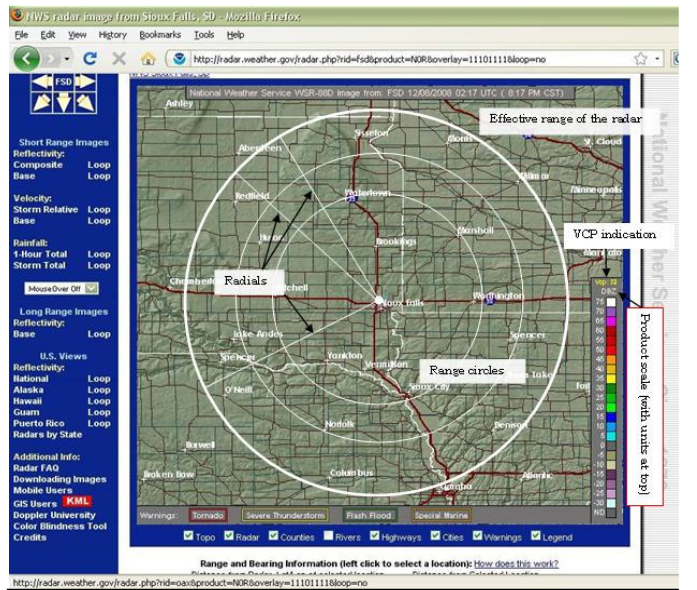

Above we see an image describing the different parts to a weather radar display on the National Weather Service website. This information applies to all radar applications on your phones as well. The radar is located at a set point in certain areas of the United States and can cover a circular range (defined by the range circles). Areas on the furthest edges of these range circles will have less accurate data due to interference with the radar beam whether it is due to dust particles, buildings, trees, etc. Explained more below, a radar beam is sent out from the radar and then bounces back off whatever it hits and returns to the radar. How much energy returns to the radar (some is absorbed by whatever the beam hits) and how fast it returns determines the distance and what type of object we are seeing. Most radars also contain a product scale which in this case above shows DBZ (decibel relative to Z) and describes the intensity of the precipitation that the beam has located. This helps us to determine where the heaviest precipitation bands are located and whether or not flash flooding may be an issue.

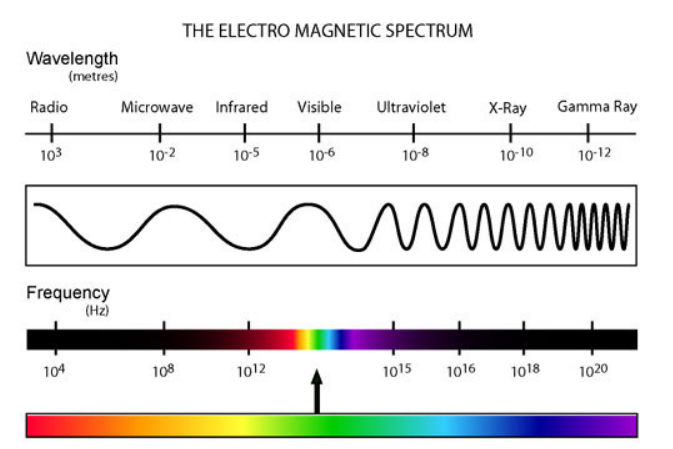

Doppler radar uses a form of energy called Microwaves, similar to the appliance we all have in our homes! The wave lengths of microwaves are longer than infrared and visible light and are close enough  to the Radio wavelength (Radar stands for RAdio Detection and Ranging). These microwaves differ from the ones we use in our appliances at home because instead of having the water droplets absorb the microwave energy and heat up, we want the microwave to reflect off of them and back to our receiver (the radar dish). Based on the type of wave sent out (depends on wavelength and frequency that the radar uses) we can tell if there is any precipitation and how big it is (which helps to tell if it is frozen or liquid precip). However, this is far from a perfect assessment as there are many things that can interfere with the radar beam and its path which can lead to false radar images and back scattering. In the image to the left, we can see the radar is picking up both buildings and insects from its radar beams being sent out!

to the Radio wavelength (Radar stands for RAdio Detection and Ranging). These microwaves differ from the ones we use in our appliances at home because instead of having the water droplets absorb the microwave energy and heat up, we want the microwave to reflect off of them and back to our receiver (the radar dish). Based on the type of wave sent out (depends on wavelength and frequency that the radar uses) we can tell if there is any precipitation and how big it is (which helps to tell if it is frozen or liquid precip). However, this is far from a perfect assessment as there are many things that can interfere with the radar beam and its path which can lead to false radar images and back scattering. In the image to the left, we can see the radar is picking up both buildings and insects from its radar beams being sent out!

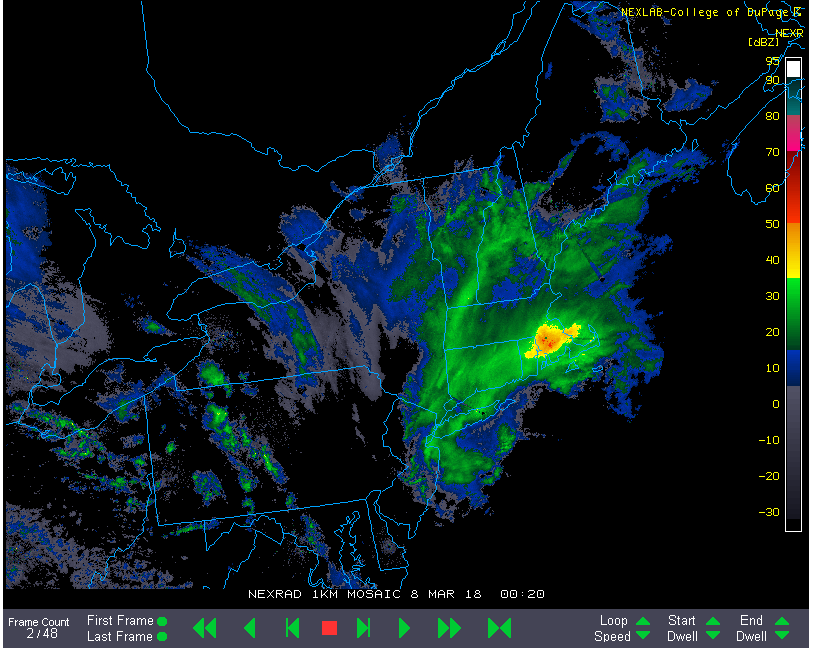

This is where it gets tricky and you need to be able to determine what is actually precipitation and how its intensity is being influenced by either radar beam scattering or other meteorological factors (such as ice crystals, hail, etc). This is especially prevalent during thunderstorms in the summer and during snow storms in the winter as hail and ice crystals in the falling precipitation will reflect the beam more intensely back to the radar.  This in turn will make the radar produce an image which shows heavier precipitation than is actually falling, this is called “bright-banding”. The image to the right here is from a winter storm on March 8th of 2018. Here we see a large area of oranges and reds in the storm. This is intense precipitation if it were all rain, however, since this is a winter storm event there was mixing and icing occurring in these regions. Since ice reflects more energy than rain/snow, it appears brighter on the radar. The radar interprets this as intense snow/rain, but it is not likely to be as intense in observation. Similar things can be seen during the summer in Thunderstorms. Sometimes we can see colors ranging into the purple range during intense severe storm outbreaks, which usually can mean there is a hail core or it could even be a debris ball if there was potential rotation! More on that in our next installment where we look at base velocity and how we can tell storm motion and if there is rotation!

This in turn will make the radar produce an image which shows heavier precipitation than is actually falling, this is called “bright-banding”. The image to the right here is from a winter storm on March 8th of 2018. Here we see a large area of oranges and reds in the storm. This is intense precipitation if it were all rain, however, since this is a winter storm event there was mixing and icing occurring in these regions. Since ice reflects more energy than rain/snow, it appears brighter on the radar. The radar interprets this as intense snow/rain, but it is not likely to be as intense in observation. Similar things can be seen during the summer in Thunderstorms. Sometimes we can see colors ranging into the purple range during intense severe storm outbreaks, which usually can mean there is a hail core or it could even be a debris ball if there was potential rotation! More on that in our next installment where we look at base velocity and how we can tell storm motion and if there is rotation!